Did you all have a good holiday season? Depression-wise, I did. New mental strategies from my therapist help me go strong. But let me tell you about someone I met during our Thanksgiving dinner party. We’ll call him Hamlet. Hamlet’s a different story.

Hamlet is Polish, and English is his second language. For 15 years, he has been without a job, his engineering credentials in Poland useless in the US. He spends his time, then and now, sitting at home, wallowing in depression without a job or a family to occupy his mind. He often calls his mother up and talks for hours on end about his feelings. He is also a devout Catholic. Later on in this story, I’ll discover that he went to a therapist years ago, whose ultimate advice was that he’d pray for him. He has been waiting for Jesus like a dog standing over his master’s dead body.

This is that state Hamlet was in when my mother asks me to help out. During the Thanksgiving party, while most people are eating in the spacious basement, she takes me aside to our host’s untouched dining room and mentions that Hamlet, like me, is going through depression. She believes I am a good enough go-getter to engage with Hamlet, share depression tips with him, and perhaps help him. I decline this offer at first. Then, for reasons I’ll get into later, I ask for more information on Hamlet so I can start a conversation with him. She obliges. After a truth-seeking mission, my mother comes back to me and tells me that Hamlet likes movies. This is a good opening— I can tell Hamlet that I’m looking for movies that stimulate feelings of depression, and I’ll appeal to his movie buff side by asking him to recommend flicks. From there, I’ll warm my wait into giving advice.

I find Hamlet outside, staring off into the rows of suburban houses while some other Polish relatives smoke and talk inside the garage. I ask Hamlet if he has a moment. He sighs and joins me in a walk, though he grumbles about not really wanting to talk. I’ll make this quick then, I say. I ask him about depressing movies, but he says he’d rather watch happier stuff. Here, I move in for the real target. I say his “I don’t want to talk right now,” sounds like the words of several (imaginary) friends of mine who also have depression (at this point in his condition, Hamlet is faking nothing. He’s a real miseryguts). I tell him of my depression, and then pull up a list of what I do to get out of depressive episodes. Around the time I reach #5, he sighs. I ask him if he wants me to stop He says yes. He thanks me, but says that it’s not as easy for him. I say it’s not easy for anyone with depression, then re-enter the bulky house, leaving him alone again.

Inside, I find my mother, my aunt, my grandmother, and Hamlet’s mother (we’ll call her Gertrude, in keeping with the theme) in the dining room. They’re all awaiting results. I tell them about my lack of success, and they thank me for trying. I leave, thinking that the whole thing’s over for now.

An hour later, I pass by that room again looking to avoid the crowds in other parts of the house. Gertrude, grandmother, and aunt are there, all shouting at Hamlet as he stands at the doorway. Hamlet looks ready to cry. The three women, when I enter, turn to me and tell me Nick, tell him that you’ve got a job, and that Hamlet needs to get a job too. Throughout that long conversation, I keep telling the three women that they’re technically right, but that they’re not helping Hamlet by ganging up on him and adding to the din of critical voices inside his head. My mother, who was smart enough not to be there, worried about this sort of thing happening. Throughout that conversation, Hamlet tries to leave, but the ladies shout for him to come back. Their shouting doesn’t stop. In this conversation, I learned about the bad psychologist, and I offer my only useful contribution to that conversation, that said psychologist was bad. I try to get Hamlet to talk more instead of just becoming the recipient of criticism. But my thoughts on internal parts and unrealized voices can’t even reach his head to fly over it. His English is simple and mine is complex. His faith is simple and mine is compromised. He finally breaks away from the women for good, and I leave too.

I talk a lot about my own depression, but not much about how to help others. That’s because I don’t know how to. Lindsay Ellis gives a good list of what not to say to someone with depression, and flat out admits she’s not sure what to say. My memory was strong enough that I remembered what not to say, but I forgot the overall message about making the situation as little about myself as possible. It’s natural for people with similar burdens to want to band. Me and you, fellow writer with depression, want to express our feeling while also helping out others. How do we do that?

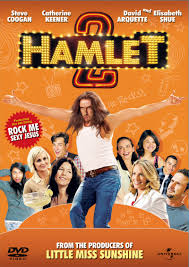

Hamlet, in this case, didn’t want to be helped. Ok, he wanted to be helped by Jesus, but in this case a higher power (or my mother, close enough) sent me, her middle son, to the man to bring tidings of free writing and Vitamin D. The Lord can be direct if She wants to be. Should I have forced myself to stay? Should I have barged in, the Big Damn Hero, to say, “You need help!” Of course not. But during the outside conversation, when Hamlet refused my email address in case he wanted to stay in contact, I thought “Well, here comes another few months of him watching TV in his underwear.” But you know who else refuses people in need: therapists. My therapist too. The session we had before this incident, he talked about how sometimes a case is not a good fit for patient or doctor, and how he had to send clients to another professional. If you want to play therapist, you need to sometimes acknowledge that there are people you can’t help for reasons that are as unfair as they are true. Hamlet was waiting for Jesus, and I am not Jesus; I barely even qualify as Luke. I can’t help everyone.

When I mentioned this incident to my therapist, he suggested that I ask why I was putting pressure on myself to help others. I really wish aunt, grandmother, and Gertrude had considered this. Hell, I wish I considered this when I started talking. Why did I want to help him? Or, more to the point, why did I put pressure on myself to help him in that particular way? I could’ve just said, “I’m here to listen.” I could’ve just talked to him like a normal person instead of like a secret agent. Or, better yet, maybe I should figure out what’s going on with myself before I start handing out advice.

I think that’s part of the reason why I write, and why I try to be the hero and maintain good relations with others: to create a fellowship.

After this incident, I can think of 5 main reasons why I write:

- Because to entertain is the best thing in the world.

- To show that I’m not worthless, that I’m good at something.

- To understand myself and my depression better.

- To emphasize with others and see what makes their gears grind.

- To use points 3 and 4 to communicate what I’ve been so poor at communicating before (ideas, depression, feelings, etc.)

All of those reasons, save for #1, concern how I interact with others. What I do to feel less alone. And that’s why I reached out to Hamlet, why I write these types of posts, why I try to be as helpful as I can in real life: to make sure people don’t go through the same things I went through.

But people are not me. I’d say that’s the flaw in the Golden Rule (blimey, I talked about religion a lot today, haven’t I?), believing that everyone is like you. And Hamlet is not like me. Same goes for you too. I can tell you what it’s like to be this writer with depression, and how that influences my writing and my character, but I’m not ready to solve anyone’s problems. If you’re looking for writing advice, then there it was. Instead of going into a project with a message to convey, and pointing that nail into the thick skulls of your readers, treat readers as human beings first, instead of means to an end of your suffering. Find out what your ideal reader likes. Talk with her, instead of to her. You can still be didactic and have messages, but books are not treasure maps where you use your decoder ring to find the solitary chest of gold in an otherwise deserted island. There’s a reason Baum wrote the entirety of The Wizard of Oz instead of just an essay on the gold standard: all the other aspects of the book make it bigger than just one economic filibuster. And if you’re going to be a writer, there are times where you’ll have to be bigger than yourself too.

Very interesting and well written. You explore a difficult topic nicely and with sensitivity. It would have been easy to not have viewed this with such introspection and balance.

LikeLike

Thanks for a well described window into depression. You do a great job at giving me a sense of what you and others experience. Very insightful piece!

LikeLike

Beautifully human. Insightful and well- written.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Writing With An Injury – Word Salad Spinner

Pingback: On Writing With Depression: The Amanda Laurens of the World – Word Salad Spinner